PRICKLY PEERS China And India Are Trying To Get Along Better

Xi Jinping and Narendra Modi are meeting for an “informal” summit

DRAGONS are lithe and prickly and cunning. When excited they breathe fire. Elephants are tubby, lumbering and shy. They never forget a slight, and when angered grow fierce and implacable. If the metaphorical animals typically used to depict them are anything to judge by, it is not surprising that China and India, the world’s two most populous countries, tend to compete more than co-operate.

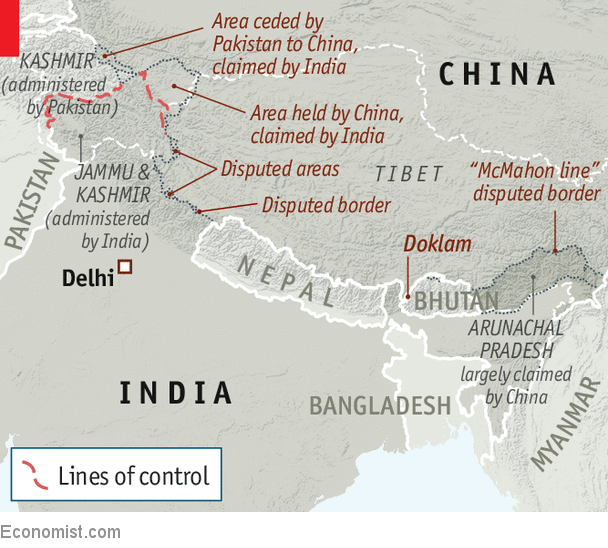

For decades each has claimed bits of the other’s territory. Each nurses a long list of irritants; each dislikes the other’s friends; each suspects the other is up to no good. Sometimes, as in a brief border war in 1962, India and China have clashed. At other times they have professed a fickle friendship. But most of the time the two giants just peer warily at each other over the Himalayas—which is why the two-day “informal” summit between their leaders, to be held in the Chinese city of Wuhan on April 27th-28th, marks a striking departure from the norm.

Both countries are billing the meeting between Prime Minister Narendra Modi and President Xi Jinping, which follows four years of rising tensions, as a historic chance to “reset” relations on a friendlier footing. If the optimistic words of Wang Yi, China’s foreign minister, are to be believed, the Chinese dragon and Indian elephant “will no longer fight with each other, but dance”.

That would be nice. The two countries are home to a third of the world’s people. Both have done well economically in recent years, China spectacularly so. Its economy is now nearly five times India’s, but the laggard is slowly catching up, even as its population is set to overtake China’s some time in the next decade. Yet, although their mostly peaceful rivalry has lacked drama, it does carry costs, not only for the principals but for the wider region.

Instead of using its clout to help calm the chronic and debilitating enmity between India and Pakistan, for instance, China has chosen to sustain an “all-weather alliance” with Pakistan—including generous military, economic and diplomatic backing—as a means to apply pressure on India. And so, instead of welcoming China’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative as a source of much-needed capital and infrastructure for itself and smaller neighbours, India has kept aloof, condemning it as a sneaky Chinese scheme to entrap unsuspecting client states in debt.

Instead of using its clout to help calm the chronic and debilitating enmity between India and Pakistan, for instance, China has chosen to sustain an “all-weather alliance” with Pakistan—including generous military, economic and diplomatic backing—as a means to apply pressure on India. And so, instead of welcoming China’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative as a source of much-needed capital and infrastructure for itself and smaller neighbours, India has kept aloof, condemning it as a sneaky Chinese scheme to entrap unsuspecting client states in debt.

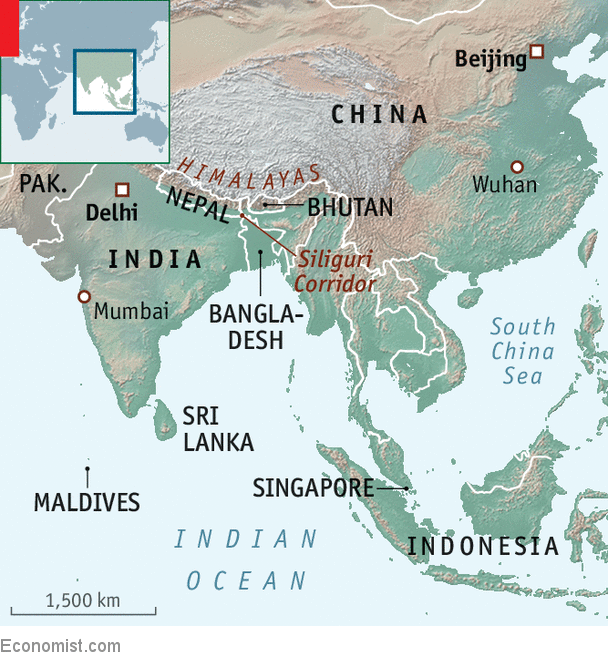

Rather than profit by opening its own territory as an obvious passage between China and the West, India has instead pushed China to seek alternative routes. And so China has intruded with growing assertiveness into places that India regards as its own natural zone of influence—with aid and trade into countries such as Nepal, the Maldives, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, and with its navy into the Indian Ocean. This, in turn, has encouraged India to bolster its position by edging away from its historical posture of non-alignment and seeking deeper defence ties with other strategic rivals to China such as America, Australia and Japan. China, obviously, finds this threatening, and so the cycle of mistrust deepens.

The Summit of Love

No one in Delhi or Beijing thinks that one summit meeting can resolve all this. “The changes of India’s China policy are only tactical, not strategic, as India’s traditional hegemonic and cold-war mentality has not changed,” sniffs Liu Zongyi, a Chinese academic, in the Global Times, a nationalist newspaper. “This is more like pressing a pause button than a reset,” chimes Dhruva Jaishankar, a Delhi-based analyst at the Brookings Institution, a think-tank. “For things to really change, China has to re-conceive how to play its role as a major power.” In other words, it has to be less of a bully, and treat its neighbour as an equal.

Yet both recognise that the drift in recent years towards escalating friction has not helped anyone, either. The biggest wake-up call came last year, when Indian troops moved to block a Chinese army road-building crew at Doklam, a high plateau where the borders of China, India and its small ally, Bhutan, meet. India, alarmed by the proximity of the area to the Siliguri Corridor, a narrow territorial isthmus linking the body of India to its eight easternmost states (see map), backed Bhutan’s claim to the disputed territory. Its forces held firm for 73 days before China backed off. Mr Modi’s government claimed victory, but China has since beefed up its garrison in the region.

The stand-off revealed more than the two countries’ relative strength at a remote frontier. The rapid escalation showed how dangerous the lack of resolution to border problems can be, and highlighted the fact that, North Korea aside, the disputes with India and Bhutan remain China’s only outstanding land-border issues. In the past both big neighbours have hinted that they would accept the simplest solution: recognising the “line of actual control” that has prevailed since 1962 as a permanent border. It may be that establishing personal trust between Mr Modi and Mr Xi is enough to make that happen.

But this will not be the only issue on the leaders’ agenda. Indian concerns with China include, among other things, its blocking of Indian membership of the Nuclear Suppliers’ Group, which “licenses” trade among nuclear powers, its refusal to allow the designation of Pakistan-based Islamist fugitives as international terrorists, and what India sees as China’s failure to reduce its gigantic trade surplus with India. For its part, China has long chafed at India’s hosting of the exiled Tibetan spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama, as well as its resistance to the Belt and Road Initiative.

Quietly and obliquely, many of these issues have already been discussed in the months of careful diplomacy leading up to the summit. It helps, to an extent, that President Donald Trump has concentrated minds in both countries through his aggressive stance on trade. Mr Xi and Mr Modi, speaking at the World Economic Forum jamborees in Davos this year and last, respectively, sounded strikingly similar tones about the importance of upholding the global economic order. If a growing realisation of their shared interests causes the pair to stop treading on each others’ feet, perhaps India and China really will learn to dance.

my husband and I did ttc spell once, I’m pregnant! It’s so easy and I would highly recommend others try this. We are thrilled! on facebook: o d u d u w a a j a k a y e

ReplyDelete