Spies Rule The Roost

In its 50th year, R&AW is at the centre of massive overhaul of intelligence apparatus

by R Prasannan and Namrata Biji Ahuja

As he enters the last lap of his first term, Prime Minister Narendra Modi is undertaking a quiet overhaul of the top echelons of India’s security establishment. In a series of moves that could change the character of governance, he is packing the security establishment with former and serving spymasters and generals.Within R&AW, which is celebrating its 50th year, the deadwood are being removed, and young and fresh minds hired.“We get critical intelligence about what the Chinese or Pakistanis are up to from [overseas] stations.”-R&AW officer

The National Security Council Secretariat, a fief of former diplomats even when headed by former Intelligence Bureau chief M.K. Narayanan, is now packed with former and serving spymasters. Its budget has been upped 10 times from a paltry Rs33 crore in 2016-17 to Rs 334 crore in 2017-18, and rules have been eased so as to make import of security equipment exempt from item-wise licence.

In a signalling gesture, the Sardar Patel Bhavan on Parliament Street has been allotted to the exclusive use of the NSC Secretariat. Other offices in the building—such as part of the cabinet secretariat, and the panchayati raj and statistics and programme implementation ministries—are moving out. In the new security regime, National Security Adviser Ajit Doval, a former Intelligence Bureau chief, will be a virtual security Czar with all security agencies and advisers reporting to him. He will be aided by four (earlier there was only one) deputy NSAs—most of them former spymasters—plus a military adviser.

Former R&AW chief Rajinder Khanna and Joint Intelligence Committee chairman R.N. Ravi, who is also the interlocutor for the Naga talks, have been made deputy NSAs. These posts were hitherto held by diplomats whenever the NSA was from the police. The other deputy NSA is Pankaj Saran, a former diplomat. Former Defence Intelligence Agency chief Lt Gen V.G. Khandare will be the new military adviser. With this, the JIC, which analyses intelligence data flowing from the R&AW, IB, Military Intelligence, Naval Intelligence and Air Intelligence, gets subsumed under the NSCS.

The Strategic Policy Group, which had been non-functional since the early days of Manmohan Singh’s second term, is being revived. It will have the chiefs of the armed forces, R&AW and IB, to make recommendations to the National Security Council. Its head will no longer be the cabinet secretary as had been the practice, but the NSA—who also heads the newly set up Defence Planning Committee and the refurbished National Security Advisory Board. The board has been pruned to four members, with P.S. Raghavan, former ambassador to Russia, as its chairman. He is aided by Lt Gen S.L. Narasimhan, a China expert who had commanded a corps on the Tibet border, former R&AW hand A.B. Mathur, and Bimal Patel, an academic.

The Strategic Policy Group, which had been non-functional since the early days of Manmohan Singh’s second term, is being revived. It will have the chiefs of the armed forces, R&AW and IB, to make recommendations to the National Security Council. Its head will no longer be the cabinet secretary as had been the practice, but the NSA—who also heads the newly set up Defence Planning Committee and the refurbished National Security Advisory Board. The board has been pruned to four members, with P.S. Raghavan, former ambassador to Russia, as its chairman. He is aided by Lt Gen S.L. Narasimhan, a China expert who had commanded a corps on the Tibet border, former R&AW hand A.B. Mathur, and Bimal Patel, an academic.

The next in line to go thus subsumed, sources say, will be the office of the principal scientific adviser, currently held by K. Vijay Raghavan under the cabinet secretariat. Another reform has been the creation of the post of the national cyber security coordinator—currently held by former Computer Emergency Response Team head Gulshan Rai—who reports to the prime minister. This office will also be made part of the NSCS.

Former R&AW hand A.B. Mathur has been made the interlocutor with the ULFA; former IB chief Dineshwar Sharma is interlocutor on Jammu and Kashmir, and another ex-IB boss, Syed Asif Ibrahim, had been special envoy on counter-terrorism in the NSCS till lately. Former R&AW chief Alok Joshi (see interview) recently retired as head of the technical intelligence gathering agency National Technical Research Organisation (NTRO); he has been succeeded by another spymaster S.C. Jha. A former IB special director, Jha was Joshi’s deputy. “It is beneficial to have a specialist on the job,” said Ajit Lal, former JIC chief. “As R&AW chief, Joshi was a consumer of intel gathered by the NTRO. When he became its chairman, he knew exactly what is expected of the NTRO by the IB or R&AW.”

Both R&AW and IB will have new chiefs in two months—K. Ilango, who was station chief in Colombo and was accused by Mahinda Rajapaksa of having managed the 2015 presidential polls in favour of Maithripala Sirisena, is being tipped to head R&AW. All the same, the name of R&AW officer Samant Goel, who has been named in the FIR in the tussle within the CBI, has also been making rounds, as also of Subodh Jaiswal, who is currently Mumbai Police chief. Jaiswal had done a stint in R&AW and had got empanelled to hold a director-general post. In the IB, the front-runners are Arvind Kumar, a 1984 batch Assam cadre IPS officer currently posted as special director, and Maharashtra Police chief Dattatray Padsalgikar. Padsalgikar, who had a long stint in the IB, was to retire in August, but has been given a three-month extension which may be extended till December, when the incumbent Rajiv Jain retires.

MEANWHILE within R&AW, which is celebrating its 50th year, the deadwood are being removed, and young and fresh minds hired. In the largest clean-up drive since the days of Morarji Desai, who sacked a third of his spies, the Modi regime has marked more than 70 senior and mid-level officers for “compulsory retirement.”

The exercise, personally supervised by R&AW chief Anil Dhasmana since last year, will involve giving pink slips on grounds of “non-performance” and “doubtful integrity”. A dozen of those marked, four holding joint secretary rank, have been shown the secret door. If the sack of the 1970s was undertaken with a view to blunting R&AW’s effectiveness by a prime minister who hated covert operations, the present exercise is being undertaken by a gung-ho prime minister who wants to make the agency leaner and sharper. As former R&AW special secretary Pratap Heblikar told THE WEEK, “The years 2007-14 were the agency’s worst with mediocre chiefs, political interference, nepotism and corruption ruling the roost. The period witnessed the demise of R&AW at the hands of a mafia.”

The period also witnessed a most shameful sex scandal when senior officer Nisha Priya Bhatia, who was working in R&AW’s training pad in Gurugram, went to court seeking prosecution of the officers in R&AW’s sexual harassment committee, which, in 2008, found “no proof” for her complaints. The government declared her a person of unsound mind, after she tried to immolate herself in front of the prime minister’s office, but withdrew the statement after a court order. The Supreme Court recently issued notices to the R&AW chief and others.

The period also witnessed a most shameful sex scandal when senior officer Nisha Priya Bhatia, who was working in R&AW’s training pad in Gurugram, went to court seeking prosecution of the officers in R&AW’s sexual harassment committee, which, in 2008, found “no proof” for her complaints. The government declared her a person of unsound mind, after she tried to immolate herself in front of the prime minister’s office, but withdrew the statement after a court order. The Supreme Court recently issued notices to the R&AW chief and others.

The Bhatia case was followed by former R&AW hand Major General V.K. Singh’s revelation in a book about misuse of secret funds and corruption in equipment buys—he is now facing prosecution for revealing secrets. Then came former officer R.K. Yadav’s book Mission R&AW which raised corruption and misconduct charges against several former chiefs—particularly Ashok Chaturvedi (2007-2009), who is alleged to have tormented Nisha Bhatia, and S.K. Tripathi (2011-2012) who, Yadav alleges, “eroded the working culture of R&AW and made it an agency of municipality level”.

There was also the case of Brig Ujjal Dasgupta being linked to American spy Rosanna Minchew, and the recall of the Colombo station head who had been honey-trapped by a Chinese woman. The worst stink raised by Yadav is about two officers caught on spy camera in 2013, having sex in the office.

The period also witnessed a series of setbacks and gaffes. The worst was when Pakistan pointed out that the R&AW-made list of wanted terrorists that India had handed over to it contained names of three men who were in Indian custody. India had to eat the humble pie when Pakistanis played the gracious victim—they played it down, apparently in return for an old favour. R&AW had earlier saved the life of president Pervez Musharraf with a timely warning about an assassination plot. Such courtesies are common in the world of spies (see story on page 58).

There are those who argue that during the down period, R&AW’s attention was on the east. As the 2009 fiasco over the Indo-Pak statement in Sharm-el Sheikh revealed, India had, as a matter of policy, scaled down operations in Pakistan. “But, we got ULFA chief Arabinda Rajkhowa during this period,” pointed out an Army officer who had liaised with R&AW in the east. “Our boys [R&AW operatives] in Bangladesh worked on Rajkhowa to surrender to the Bangladesh Police, who handed him over to India.”

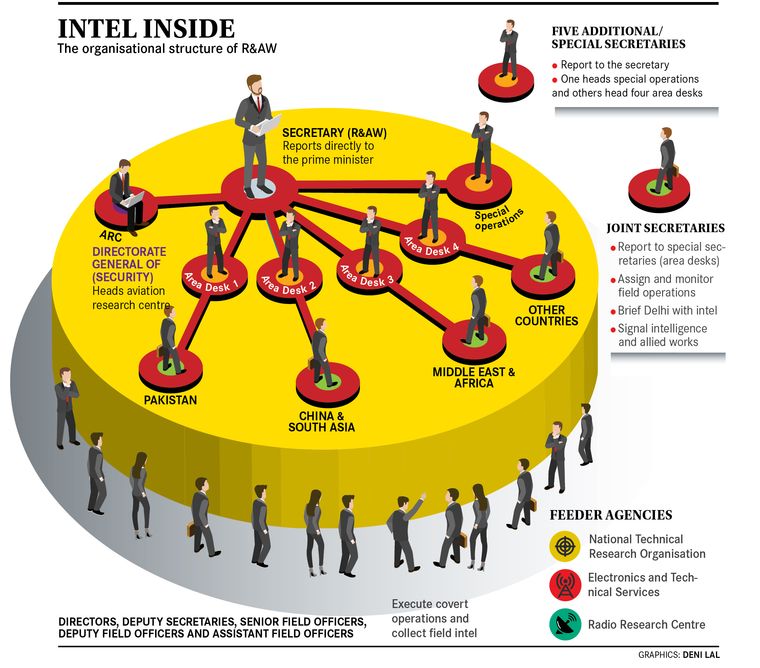

THE MAIN PROBLEM that is causing failures or setbacks in the western theatre, R&AW hands admit, is one of legacy. R&AW is facing a shortage of personnel; it needs 9,000 hands, but has only 7,500 to 8,000. The shortage is at the level of joint secretaries, directors and deputy secretaries—about 40 posts at these levels are vacant. There are few on the rolls who can speak Pashto, Khowar or Kohistani, the tribal tongues of Pakistan’s northwest.

Moreover, an Islamophobic mindset that had gripped the security establishment has led to recruitment of too few Muslims. (Asif Ibrahim, who retired as IB chief last year, is India’s first Muslim spymaster.) The result is there are few who can be sent to Pakistan, Pakistan-occupied Kashmir or Afghanistan. Pointed out former R&AW chief AS Dulat: “I am a man from the IB, and I feel that nothing can replace human intelligence. The more, the better.’’ Dulat had tried to recruit Muslims—especially after the 1999 Indian Airlines Flight 814 hijack which took place during his term—but found a deep distrust even among instructors. They found it easier to teach Urdu to Sikhs and Hindus, groom them into Muslim aliases and launch them into Pakistan and PoK. “The agency needs experts in Persian, Arabic, Dari, Pashto, Urdu and Kashmiri,” said Dulat.

Islamophobia has also led to a mindset that discourages making use of double agents, a practice that all spy agencies have been following even through the years of classic Russo-American Cold War. “I have seen officers reject the idea of a double agent, saying he works for the ISI or another hostile agency,” said Dulat. “I used to tell them that this was exactly why we needed him. We are not looking for angels.”

Indeed, there are bright boys and girls wanting to serve in intelligence jobs on short-term basis, but they are hampered by the fact that after serving the contract period, they cannot get even an experience certificate. Thus, the agency is forced to recruit, even for short terms, from the armed forces, police, post and telecom. “There is a need to tap the talent which exists in the outside world and create some kind of a certification process for those hired on contract basis,” said Joshi. “Other countries have found ways of employing youngsters. We should look into them.”

The successes in the east also highlight the importance of humint. The agency has enough speakers (Hindus, Buddhists and Christians) of Bengali and the northeastern hill tongues who can penetrate the underground groups. But there are too few Muslims to do the same in the western theatre.

WRANGLES over postings are another problem. Trying to be fair to all, bosses often post techies and crypto-experts to overseas action stations where they prove to be flops, while general duty operatives while away their time pushing files in the office. The foreign service, too, resists R&AW hands coming and occupying posts which they think are theirs, especially in friendly capitals. “They ask what intelligence is to be gathered in Paris or Brussels,” pointed out a R&AW officer. “But we get critical intelligence about what the Chinese or Pakistanis are up to from these stations.”

The best example is how R&AW learnt of Pakistan’s Siachen plans in 1984 when it heard about a bulk order for snow-boots placed by Pakistan with a European manufacturer (see story on page 58). Moreover, stations like Vienna, Paris, London and Brussels are hubs of agents and double agents from all over the world who exchange tips for money or as favour.

Broader policies followed by changing regimes also affect operations. “What is required is a foreign policy that supports and takes forward the organisation, instead of tying its hands,” said Sanjiv Tripathi, the longest serving R&AW chief. “The MEA is handling that part of Kashmir which is occupied by Pakistan, and the home ministry is handling the part which is under India. But is it not a reality that the entire J&K, including PoK, is part of India? The population in PoK is also ours. R&AW should carry out psychological operations to expose this discrepancy through seminars, articles and discussions.” Tripathi believes that Pakistan’s step-motherly treatment of its minorities, particularly the Pashtuns, Sindhis, Baluchis and Baltis, offers excellent ground for hosting Indian agents. However, very little is being done, except in PoK.

There has been some energisation of the western theatre in the recent months. Though the Taliban and its myriad branches are still beyond its reach, R&AW is learnt to have penetrated the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq. This has led to the recent successes in getting Indian hostages released, and even foiling of a major terror hit in Delhi last September. R&AW stumbled on the plot when it spotted a suspicious transfer of $50,000 from Dubai to Afghanistan. It tracked the recipient and nabbed him when he landed in Delhi.

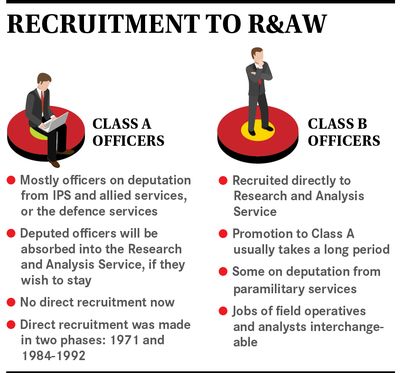

The dominance of the police service is a problem that has been plaguing the agency for decades. Non-police officers point out that due to their training and mannerisms, the police types stand out in crowds of diplomats and would be detected. “R.N. Kao’s idea was to make the R&AW a multi-disciplinary body with intake from various services, and not just police,’’ said R. Banerji, former special secretary who headed a task force on intelligence reform in the IDSA, a think tank of the defence ministry.

The exposure of financial and other scams in recent years has made many officers think that the agency needs parliamentary oversight, like in other democracies. “This will ensure that they are covering all the charter of duties assigned to them,” said Tripathi. “It would also ensure proper coordination and prevent corruption from seeping in.”

Parliamentary oversight by no means would entail disclosure of operational details, assured Banerji. “It would be only administrative oversight, making the agency answerable on fulfilling their charter of duties and utilising the resources in the right manner,” he said. Heblikar agrees: “There is need to remove the police leadership. R&AW should have parliamentary approval and be subject to parliamentary oversight.” In 2011, Manish Tewari of the Congress had moved a private member’s bill for providing legal status to IB, R&AW and NTRO. The bill lapsed in 2012.

All are agreed that R&AW has had more successes than setbacks. Dulat proudly recalled how ISI chief Asad Durrani told him: “You people are better than us, you are more professional.’’ Durrani also told him about how G.S. Bajpai, who was R&AW chief in 1991-92, had impressed him. “‘I could sense this man was superior to me,’ Durrani told me,” Dulat told THE WEEK.

As former chief Hormis Tharakan, who attempted the first clean-up after the Rabinder Singh and Ujjal Dasgupta episodes, pointed out, “R&AW was created from scratch and went on to reach rare heights. An important factor in that rapid rise was the personality of the founding fathers and the rapport they enjoyed with the political leadership. I think R&AW has adapted itself to changing ground realities admirably.”

No comments:

Post a Comment