Crude Oil Price: In Saudi-Russia Oil Price War, India Is A Big Winner

NEW DELHI: Oil price shocks always divide the world’s economies into winners and losers, sometimes producing lasting geopolitical change -- and this time is unlikely to be different. But to misquote Tolstoy, every oil crisis distributes happiness and unhappiness in its own way.

Crude’s biggest drop in three decades on Monday coincided with the spreading coronavirus, slow growth in China, a wave of de-globalisation affecting trade, and the emergence of the US as the world’s largest oil producer. Even for some consumer nations, gains from lower oil prices may this time be overwhelmed by the collapse in demand caused by Covid-19.

Perhaps the biggest worldwide change, though, is that inflation and interest rates are already at rock bottom. That means central banks may have very little capacity to cushion the deflationary effects of falling oil costs, according to Gabriel Sterne, head of global strategy services at Oxford Economics, a UK consultancy.

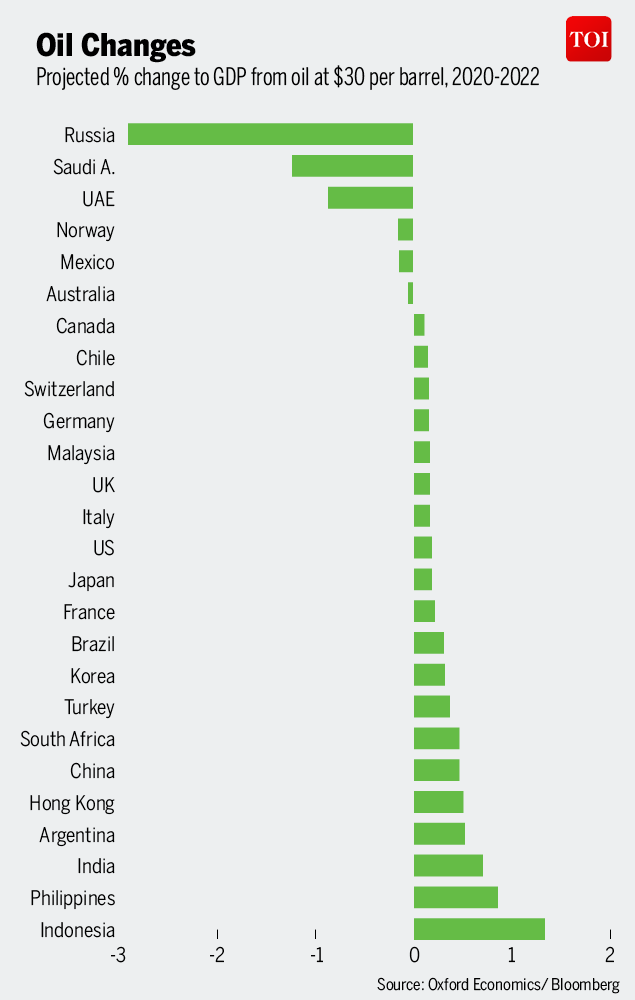

It’s hard to predict the impact of sub-$30 oil on governments around the world. Importing nations in Asia and central Europe would normally be expected to win, and major producers in the Middle East, northern Europe and the Americas to lose. But it’s not that simple.

Asia: Winners

China benefits from lower oil prices as a major importer, but this time it may take a while for the effects to materialise: It already has high stockpiles of oil and liquid natural gas, while the coronavirus is hindering travel and manufacturing and creating uncertainty.

Under those circumstances, excessive volatility in the markets may hinder China’s economic recovery, as it needs stability across the globe to prevent further shocks to supply chains. Those concerns were on full display on Monday, when the foreign ministry took the unusual step of commenting on commodity market developments.

The dramatic fall in oil prices also could have political consequences for friendly countries ranging from Iran to Venezuela -- a headache Beijing doesn’t need.

India, the world’s third largest crude consumer, should be among the big beneficiaries since its import bill will fall significantly. Cheaper oil could also help Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government by allowing it to increase taxes on fuels, rather than pass the entire benefit of the price decline to consumers. This couldn’t come at a better time for Modi, whose government is under pressure over slowing growth and the biggest bank failure in India’s history.

Lower oil prices are also generally good for resource-poor Japan, with cheaper gas helping consumers hit by a crisis of confidence over the coronavirus and a damaging sales-tax hike. It means lower costs for businesses as well, potentially supporting profits through a looming downturn.

But the volatility is a double-edged sword. The dramatic fall on Monday helped propel a flood of haven-seeking funds into the yen, pushing it to heights not seen in more than three years. And cheaper fuel will make it even harder for Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to reach his inflation targets, which he’s already struggled to hit despite unprecedented monetary easing.

No comments:

Post a Comment