Indian army soldier during a battle with armed Pakistani terrorists

More soldiers are dying as the prime minister fetishes the army and draws political capital from military operations while resisting peace efforts and doing little to actually strengthen defence

During the Kargil conflict in 1999, the Indian Army was mounting costly uphill attacks to evict Pakistani infiltrators from our side of the Line of Control (LoC), which divides the disputed state of Jammu & Kashmir (J&K). Tempers were running high in the formation in which I then served. To make the Pakistan Army pay a price too, we staged a carefully planned raid on one of their forward positions one night, overrunning it and inflicting heavy casualties on the defenders.

Inevitably, Pakistani retaliation followed, and then Indian counter-retaliation, but New Delhi stayed silent. These were small-unit, tactical operations that good armies conduct in wartime as a matter of course. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government, led by Atal Behari Vajpayee at the time, did not believe it proper to politicise them for electoral benefit.

How things have changed. This weekend, Indian colleges and universities will celebrate “Surgical Strikes Day”. Ordered by Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s BJP government, this will tom-tom a one-night operation two years ago, when Indian commandos raided four Pakistani forward positions across the LoC and returned unharmed. The commandos credibly claim to have killed 40 separatist militants and two Pakistani soldiers. The Pakistan Army says the raids never happened.

The Hindu nationalist BJP, which faces crucial state elections this year and a general election in early 2019, clearly believes this is the time to play the nationalist card and remind voters of how it has taught Pakistan and militant Kashmiri separatists a lesson. This also fits neatly into the BJP’s anti-Muslim politics. Just months after the surgical strikes, Modi rode a wave of jingoistic fervour to sweep the elections in Uttar Pradesh, India’s largest and most politically consequential province. The BJP believes this gift will keep on giving.

Towards that end, lower-level BJP leaders keep posturing grotesquely around the issue of disciplining Pakistan. After an Indian soldier’s throat was barbarically slit last week on the border with Pakistan, Defence Minister Nirmala Sitharaman boasted on a popular television show that the Indian Army was beheading Pakistani soldiers too, but quietly.

In making this reprehensible claim, Sitharaman became the first leader from either country to confirm the beheading or mutilation of enemy soldiers. Despite ample evidence, Pakistan denies mutilating Indian soldiers. And the closest an Indian leader has come to admitting to beheadings was in 2013, when its current foreign minister, Sushma Swaraj – then the opposition leader – declaimed that if the Congress government of the time was unable to recover the recently decapitated head of an Indian soldier, the army should bring back 10 Pakistani heads.

The 1949 Geneva Convention, to which India is a signatory, bans the “despoiling” of dead bodies. That Sitharaman could make such a statement without her party disowning it suggests electoral advantage weighs more in the BJP’s calculations than India’s credibility as a moral force.

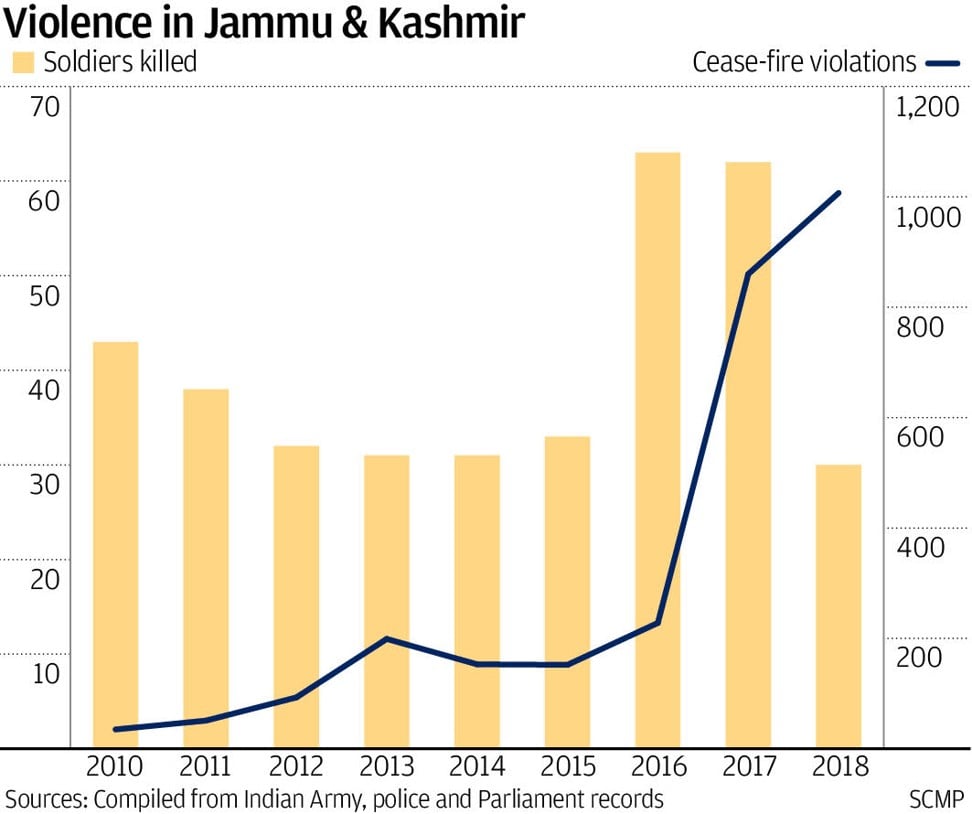

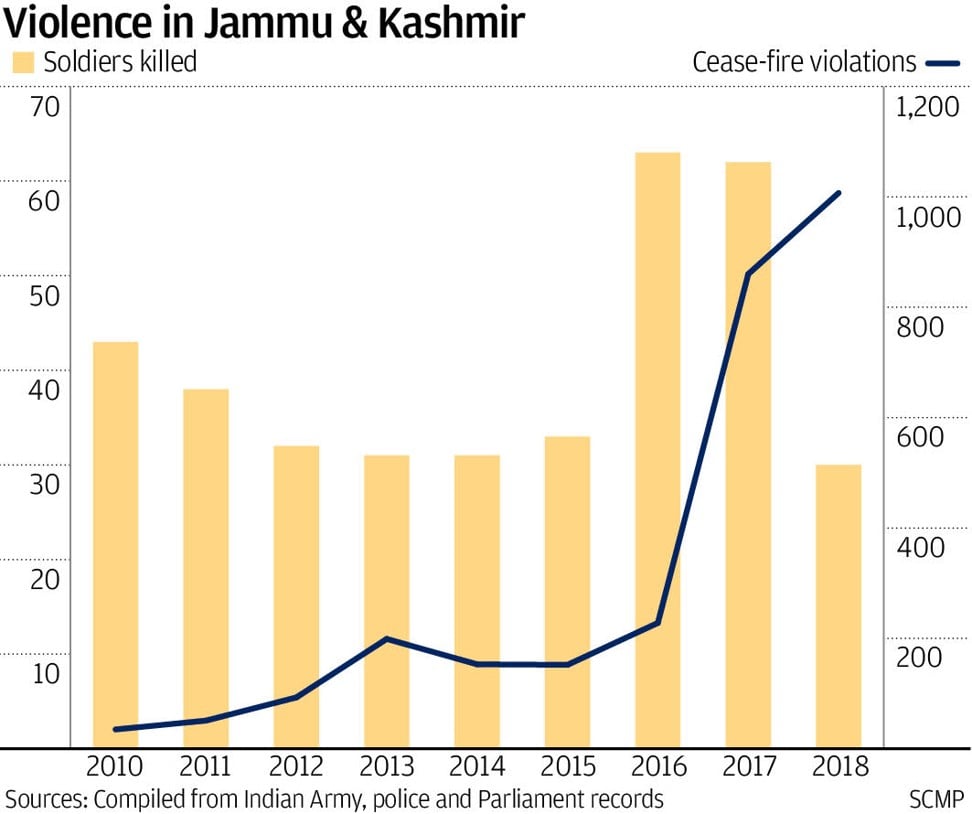

Meanwhile, on the ground in J&K, there is little evidence that Team Modi’s bluster or the surgical strikes of 2016 have achieved the BJP’s objective of “teaching Pakistan a lesson”. A decade-old LoC ceasefire has collapsed into renewed bloodshed, and a simmering Kashmiri separatist insurgency has blazed back into life. From fewer than 200 ceasefire violations in 2013, the year before Modi became prime minister, there have already been more than 1,000 this year. During each of the past two years, twice as many soldiers were killed in J&K than in 2013.

In the four years since Modi took over, 219 soldiers have been killed in Jammu and Kashmir compared with the 144 who laid down their lives in the five years under the previous government

When Modi took power, there were only 150 armed militants in Kashmir. But recruitment has been spurred by the growing alienation that stems from the anti-Muslim climate across the country – such as the lynching of suspected beef traders in several states. In the past four years, some 700 militants have been killed and the numbers keep rising, as funerals of dead fighters often see other youngsters pledging themselves to the gun. That has transformed a Pakistan-fuelled insurgency into a predominantly Kashmiri one.

After three years of violent civil protests from 2008-10, violence was declining under the previous government. But in the four years since Modi took over, 219 soldiers have been killed in Jammu and Kashmir compared with the 144 who laid down their lives in the five years under the previous government.

But while the BJP politicians keep posturing, the Indian Army pays the price on the ground. This week, Sandeep Singh – one of the commandos who returned unscathed from the “surgical strikes” of 2016 – was killed while battling militants infiltrating across the LoC. Yet the Indian Army chief, General Bipin Rawat, declared this week that another round of surgical strikes would do no harm.

While fetishising the Indian soldier, the Modi government has, in fact, done little for the army. It has operated without functional bulletproof jackets and helmets, which are only now being issued. With no progress on buying an adequate rifle, soldiers often choose to fight with Kalashnikov rifles taken from dead militants. Nor is the government allocating more money to the army: as a percentage of government spending, defence budget allocations are at a 55-year low.

And with 83 per cent of that budget going on manpower and operations, only a pittance remains for modernising equipment. In March, a senior army general lamented to a parliamentary defence committee that 67 per cent of the army’s equipment was outdated. Previous governments share the responsibility for this dismal state of affairs, but Modi, who aroused soldiers’ hopes with promises of real attention, has disappointed them with how little has changed.

Within the army, there is growing awareness that it cannot indefinitely remain a manpower-heavy counter-insurgency force. General Rawat – appointed chief for his credentials as a counter-insurgency specialist – has initiated a wide-ranging study that seeks to shift expenditure from manpower to equipment. But for this, peace must be restored in Kashmir.

Lieutenant General Deependra Singh Hooda, who commanded the army in the restive province for more than two years, publicly declared that security was adequate for a political outreach to resolve what was essentially a political problem. Vajpayee, who was prime minister at a much more turbulent juncture – with the Kargil conflict, and a near-war in 2002 – reached out to Pakistan in 2003 and implemented a ceasefire that brought a decade of relative peace. His successor, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, initiated back-channel contacts with Kashmiri separatist politicians and a Kashmir-resolution dialogue with Pakistan that fostered years of peace. But Modi apparently fears that his constituency would see any outreach to Pakistan or Kashmir as placating Muslims.

Ironically, conditions are propitious within Pakistan for meaningful dialogue. The country’s army chief and power centre, General Qamar Javed Bajwa, has signalled unmistakably that he would support a meaningful peace dialogue. In newly elected prime minister Imran Khan, Bajwa has a political leader the army trusts – unlike Khan’s predecessors, Nawaz Sharif and Asif Zardari. But New Delhi is failing to seize the moment and initiate dialogue. After agreeing last week that the two foreign ministers could meet in New York – the first contacts at that level since 2015 – New Delhi backed off within 24 hours.

The growing nationalist fervour in many parts of India, particularly the north, might allow Surgical Strikes Day to seem a success. Within the Indian Army, however, which boasts more impressive feats of arms – including hard-fought campaigns in the two world wars that claimed 34,000 and 24,000 lives, respectively, and which liberated Bangladesh from Pakistani military occupation in 14 days in 1971 – there is disdain for this political jamboree. For the soldiers, September 29, 2016 was just another day on an increasingly bloody line of control.