Pakistan Economy: A Reality Check

Pakistan’s recent bluster is in stark contrast to the precarious state of its economy — a GDP less than a tenth India’s, and buried under a mountain of international debt. This is what macroeconomic indicators show

Ever since Parliament revoked the special status enjoyed by Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan’s Prime Minister Imran Khan and his colleagues in government have warned of a potential military conflict, even nuclear war, with India.

On Thursday evening, the Ministry of External Affairs condemned the “highly irresponsible statements made by the Pakistani leadership on matters internal to India… (including) references to jihad and to incite violence in India”.

Early Thursday morning, Pakistan had tested its surface-to-surface ballistic missile Ghaznavi, which is capable of delivering multiple types of warheads upto 290 km, after having shut down, the previous day, the three air routes above Karachi until August 31.

On Tuesday, Pakistan’s Science and Technology Minister Fawad Chaudhry, a close aide of Imran’s, had posted on Twitter that his Prime Minister was “considering a complete closure of airspace to India, a complete ban on use of Pakistan land routes for Indian trade to Afghanistan”, and boasted that “Modi has started, we’ll finish!”

If Pakistan does close down its airspace to India completely, flights to/from airports in the Gulf, Europe and the United States from/to India could get longer by perhaps 70-80 minutes. When Pakistan took this step from February 26 to July 16 in the wake of the Balakot airstrikes, Indian carriers lost around Rs 700 crore. However, Pakistan itself suffered more — losing around $50 million in revenues, which was roughly five times the cost to India.

Pakistan’s bluster and threats of hurting India financially come at a time when its own economy is in a perilous state, teetering on the brink of collapse, with no room for losing any revenue.

India, Pakistan Compared

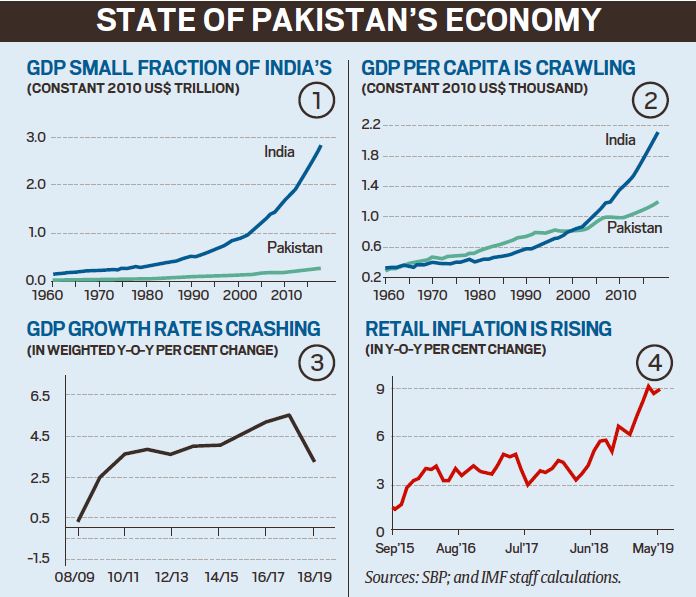

According to the World Bank, Pakistan’s gross domestic product or GDP stood at $254 billion at the end of 2018; for India, the figure was $2.84 trillion (see chart 1).

To put this in perspective: not only was the Indian economy more than 11 times Pakistan’s last year, if India grows at 7% in 2019, it would add almost $200 billion in just one financial year — or almost 80% of Pakistan’s 2018 GDP.

Another way to compare: India’s GDP was at the level where Pakistan’s is today 44 years ago — in 1975.

Caveat: aggregate variables like the GDP often do paper over more granular details. For instance, thanks to the wide gap in total population, India’s GDP per capita overtook Pakistan’s only in 1999.

State of Pak Economy Now

Pakistan’s economy has had several fluctuations but on the whole it has grown at an average of 4.3% — a rate similar to the so-called Hindu rate of growth — between 2000 and 2015.

But its economic momentum is fast slipping (see chart 3); Pakistan is expected to grow at less than 3% in both 2019 and 2020, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). To make matters worse for the average Pakistani, slower growth hasn’t abated the sharp rise in retail inflation (see chart 4), which was close to 9% in May 2019.

Also, Pakistan is facing a dire financial situation. As chart 5 shows, the government’s fiscal balance — akin to the fiscal deficit in India and representing the overall level of borrowing by the government — has been rising. According to a Bloomberg report published this week, it is already at 8.9% of the GDP — reportedly the highest in almost three decades.

Owing to the weak state of the economy, Pakistan’s exchange rate has continued to plummet — from levels of 140 to the US dollar in the middle of May, it has fallen to nearly 157 this week. (see chart 6)

Drowning In Debt

Pakistan has a dubious record of borrowing money to sustain itself. As chart 7 shows, as of March 2019, the country’s outstanding debt was more than $85 billion (approximately 6 lakh crore in Indian rupees). It has taken loans from a very large number of countries in Western Europe and the Middle East. Its largest creditor is China.

Apart from individual countries, Pakistan has also taken substantial loans from a whole host of international institutions. In May this year, Pakistan reached out to the IMF for the 23rd time in its existence, seeking a $6 billion bailout. The Pakistan government’s revenues must go up by a whopping 40% in this financial year to meet the IMF’s loan conditionalities.

What Ails Pak’s Economy

In its July report on the country, the IMF was scathing: “Pakistan’s economy is at a critical juncture. The legacy of misaligned economic policies, including large fiscal deficits, loose monetary policy, and defence of an overvalued exchange rate, fuelled consumption and short-term growth in recent years, but steadily eroded macroeconomic buffers, increased external and public debt, and depleted international reserves”.

It also underlined some structural weaknesses that have never been addressed — these included a “chronically weak tax administration, a difficult business environment, inefficient and loss making SOEs (state-owned enterprises), amid a large informal economy”.

The IMF warned that “without urgent policy action, economic and financial stability could be at risk, and growth prospects will be insufficient to meet the needs of a rapidly growing population”.

But, as several Pakistani analysts contend, the fundamental reason for Pakistan’s broken economy is its dysfunctional political system which still runs on rent-seeking and patronage, and is largely devoid of transparency and dispersed institutional autonomy.

No comments:

Post a Comment