In the Budget of 2022 presented by Union Finance Minister (FM) Nirmala Sitharaman in early February 2022 allocated a total of 70,23 billion USD to the defence budget for the year 2022-23, which is roughly 13.3 percent of the national budget. The share allocated for Research and Development (R&D) in the latest budget stands at pitifully small sum of 1.24 billion USD, which is 1.7 percent of the total defence budget. An allocation of 25 percent of the R&D budget at a sum of 310 million to private sector industries, start-ups and academic institutions is not just worryingly, but laughably small. This figure and the entire R&D budget are being treated as a significant allocation. Consider Defence Minister (DM) Rajnath Singh’ statement on social media following FM Seetharaman's budget speech: “Substantial amounts have been allocated towards Research and Development in several sectors including Defence. The proposal to reserve 25 percent of the R&D Budget for Start-ups and Private entities is an excellent move.” Reassuringly, the Indian government has also sought to allay fears of private industry that it will extend guaranteed orders and source equipment. The private industrial enterprises that are likely to gain from the government’s acquisitions will include Tata group, Mahindra Defence, Kalyani group, Larsen and Toubro, Adani Aerospace & Defence, VEM Technologies, Tara Systems and Technologies, SEC Industries, Cyient, Alpha Design, Astra Microwave Products, Sigma Electro Systems, Economic Explosives, MKU, SSS Defence and Indo-MIM.

An allocation of 25 percent of the R&D budget at a sum of 310 million to private sector industries, start-ups and academic institutions is not just worryingly, but laughably small. This figure and the entire R&D budget are being treated as a significant allocation.

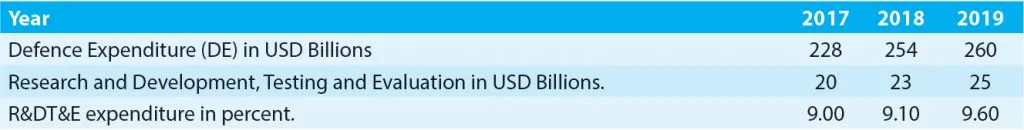

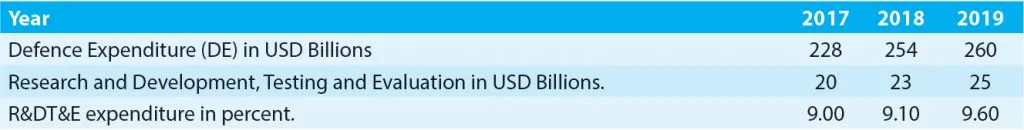

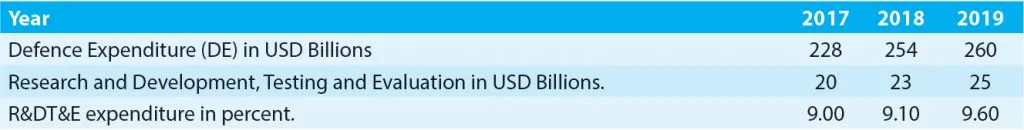

To be sure, the figure of 1.24 billion potentially excludes expenditure in strategic sectors such as nuclear and missile related R&D. Nevertheless, the R&D budget is too small by any standard compared to major military spenders across the world explaining why India lags behind in building a credible and capable domestic defence industry. The foremost test for India will have to be how its expenditure on R&D compares with China. A glance at Peoples Republic of China (PRC)’ spending on defence R&D in Table 1 will give the reader a glimpse of why India will struggle to compete effectively with one of the world’s major military powers and a neighbour against whom India faces serious military competition. Between the years 2017 and 2019, the Chinese spent roughly 9 to 10 percent of their defence budget on defence R&D as shown in Table 1. The data given below is for the three years between 2017-2019 drawn from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute’ 2020-21 report. All data in Table 1 has been converted specifically by the author to round figures with only slight variation drawn from data in SIPRI’s “A New Estimate of China’s Military Expenditure” authored by Nan Tian and Fei Su. For the years 2020 to 2021, the author was unable to access data. Despite this limitation, readers should note that the differential in the amount spent on R&D by the PRC is unlikely to be great for years 2020 and 2021 from the data shown in Table 1.

Even if the SIPRI data from Table 1 is considered a very conservative estimate, India still stacks up poorly against the Chinese in relation to defence spending on R&D and if one were to go by Indian data, India fares even worse than what SIPRI estimates about China’s budgetary allocation for defence R&D. Indeed, data obtained by the Lok Sabha Standing Committee on Defence 2019-2020 put the PRC’s R&D at 20 percent of the Chinese defence budget. That figure is twice as high as the SIRPI estimate as shown in Table 1. The MoD in its submission in the 2019-20 report stated that the DRDO – India’s leading defence R&D organization was consistently allocated 5-6 percent (very likely excluding what the MoD calls “strategic schemes” or strategic sectors) of the defence budget. This figure would still be roughly two times less than the SIPRI’s estimate and four times less than the Lok Sabha Standing Committee’ estimate on China’s allocation for defence R&D. However, in the current defence budget of 2022-23, R&D allocation is less than 2 percent of the total defence budget revealing an even greater differential. In the absence of greater budgetary support for defence R&D, the government and the MoD have sought other avenues. In the Lok Sabha Standing Committee report 2020-21, the MoD again noted in a quest to gain more technology, the Modi government which announced a 74 percent hike in Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in 2020 through the automatic route, will offset or compensate for limits on budgetary support for defence R&D by attracting “…cutting edge defence technologies”. Although evidence for such gains is unclear and the decision to hike FDI to 74 percent from 49 percent will take more time to bear fruit or if it is as attractive to foreign vendors to dole out high-end technology as the MoD claims.

In the current defence budget of 2022-23, R&D allocation is less than 2 percent of total defence budget. In the absence of greater budgetary support for defence R&D, the government and the MoD have sought other avenues.

If the Indian government does not spend as much on defence R&D through its government run defence research institutions, are Indian private sector companies making up for lack of governmental investment? Here the data is even more scant or at least obscure. It is hard to find concrete evidence on how much investment Indian private sector companies plough into in-house defence R&D. For instance, India’s largest private engineering company and a leading player in defence hardware development and manufacturing Larsen and Toubro (L&T) does have in-house R&D investments based on the revenue it earns, yet the precise amount is unknown. Further, the incentive for in-house R&D, especially in defence, as one senior L&T executive averred, must be subject to tax deduction and treated on par with government funded defence R&D programmes, if defence indigenization is to be consolidated in the long term and private enterprise is to pick up slack for low government funded defence R&D. It is entirely possible, L&T and other Indian private enterprises involved in the development and production defence equipment do not want to divulge their internal R&D investment in the interests of corporate confidentiality and secrecy. Thus, unless more information is available in the public domain establishing the scope, nature and pattern of in-house private sector investments in defence R&D will remain speculative and indeterminate.