Why India Should Look To Design And Build Its Own Jet Engines

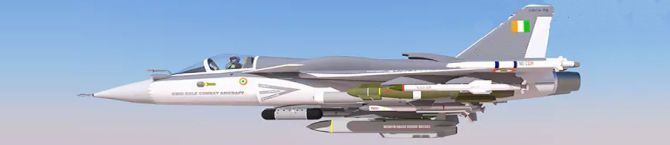

An advanced indigenous Turbofan could well power the upcoming Twin Engine Deck Based Fighter

While GE and Hindustan Aeronautics Ltd signing a memorandum of understanding to jointly produce GE’s F414 engine for HAL’s TEJAS MK-2 fighter planes is welcome, complete transfer of technology is not a done deal. “The agreement includes the potential joint production of GE Aerospace’s F414 engines in India, and GE Aerospace continues to work with the US government to receive the necessary export authorization for this," read a GE press release on the subject.

Two things stand out. For one, joint production of the engine in India is still only a possibility, not a definite commitment. The US government’s authorisation for the transfer of the technology to India has not been received yet, despite Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to the US last week. This indicates there is resistance to such sharing of technology. As it is, the agreement that has been reached seeks to expand the scope of the technology transfer to 80% from 58% in 2012. Certain vital parts would not be made in India, nor their technology shared.

There is probably a case for India to try and develop its own engines for both civilian aircraft and fighter jets. This would need a lot of engineering and plenty of funds. India has the engineering talent needed for this. The government should provide the funds. The world could do with a fifth major supplier of aircraft engines in addition to GE, Rolls Royce, Pratt & Whitney and CFM-Safran. This could be a joint venture between HAL and BHEL.

The GE-F414 is a tried-and-tested engine for fighter aircraft. The US Air Force’s most advanced fighter jet, the F35, uses an engine from Pratt & Whitney, the F135. The engine that GE and Rolls Royce were making for the F35 was dubbed F136, but it was not completed because its final iteration was not funded by the US government. The point is that while the GE-F414 is an excellent engine, better ones are being made, and if India is to achieve strategic autonomy, it must have its own fighter aircraft engines, whose parts are designed and manufactured within the country, using technology that is not under anyone else’s control.

For the complete transfer of American defence technology to India, India would probably have to ditch all collaboration with Russian arms manufacturers. That, or the Americans must trust Indians to prevent their technology from falling into Russian hands. Is India prepared to halt Brahmos, the cruise missiles it produces in collaboration with the Russians, for example? Hardly. Will the Americans have faith in the information integrity of a military industrial complex in which Russians have a sizeable role? Probably not.

Indigenous jet-engine capability is eminently desirable. If we start today, a decade from now we will probably have a reliable engine for commercial aircraft. In time, the project could yield fighter-jet engines as well.

How could BHEL, the power-generation equipment manufacturer, be a potential developer of jet engines? Industrial gas turbines and jet engines are close cousins. They differ in weight and compression ratios, dealing with different levels of heat and availability of oxygen. GE, after all, makes both types of turbines.

BHEL’s Hyderabad division makes gas turbines and has previously collaborated with GE. HAL’s Koraput unit was set up to make and service engines for Soviet-supplied fighter aircraft. One option is to merge these two units and let them produce a new breed of fighter aircraft engines with or without GE. Another is to let both units independently work on developing aircraft engines by giving them appropriate funding.

India is at a unique stage of development, having entered the lower-middle-income category of nations. With a GDP of over $3.5 trillion, India can muster substantial sums to chase particular goals. Meanwhile, the cost of talent is still relatively low. While IIT graduates can command very high salaries and a large proportion of the best emigrate soon after graduation, there is still a vast pool of talent outside the IITs that can be tapped. While the cost of the materials needed for R&D is more or less the same around the world, the cost of the engineering talent differs significantly. This is where India can score significantly. R&D, ultimately, is brainpower-intensive.

But ultimately, it all hinges on there being sufficient political will to kick off such a project. Reinventing the wheel might be a waste of time. But reinventing jet engines could lead on to better models with one standout characteristic – no strings attached.

No comments:

Post a Comment